*

Before he went electric in 1965 — and drew jeers from legions of (arguably small-minded) fans in the process — Bob Dylan epitomized the hard-traveling folk troubadour, and he established this image largely on a vintage Gibson “Nick Lucas” model flat-top guitar. The young Dylan had played other Martin and Gibson models in the late ’50s and early ’60s, but in those final years of his acoustic era, before a “blonde on blonde” Fender Telecaster ushered in a whole new folk-rock sound, the “Nick Lucas” was his instrument of choice. He played this guitar in the studio and on tour from 1963 to ’66, and used it for the legendary albums Another Side of Bob Dylan and Bringing it All Back Home. And, although it didn’t appear on the covers of either of these, it is frequently seen in the many live performance tapes from the day, including broadcasts of the Newport Folk Festival in 1964 and ’65, and Dylan’s famous appearances on BBC TV in England in 1965. While, in hindsight, this Gibson “Nick Lucas” seems “just right” for the young Dylan, and has become an iconic folk guitar as a result, the model’s origins show that it is perhaps an unlikely choice for a scruffy young folky. Via

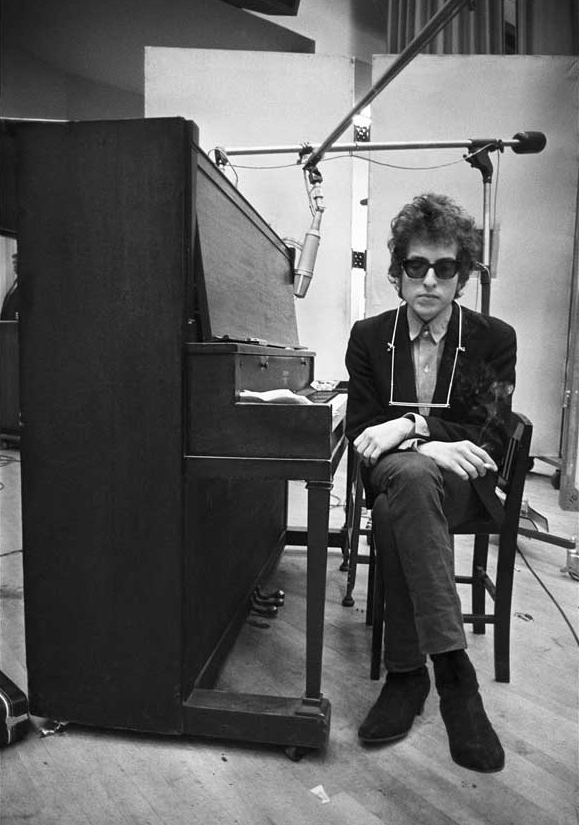

Bob Dylan At Piano During Recording Session, 1965. Bob Dylan in a contemplative mood, lost in thought behind his Ray-Bans, pausing for a break between takes at the upright piano at Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios in New York City during the sessions for “Highway 61 Revisited” in June 1965, a mere month before his electric set at the Newport Folk Festival would send Folk and Rock and Pop music into a whole new direction. –Photo by Jerry Schatzberg, Via

*

By the summer of ’65, Dylan’s stardom surpassed that of the Folk traditionalists at the Newport Folk Festival. Hundreds of adoring fans overwhelm Dylan’s car, as he basks in the attention, smiling and stating, “They’re all my friends.” But there is wave of rebellion beginning to well-up against Dylan among the so-called Folk purist fans. They see him as already being a sell-out, having moved over to the side of the establishment. In their eyes, Dylan is now just another cog in the wheel. The stage is now set for the epic event that will forever be remembered as– When Dylan Went Electric. So what inspired Dylan to go electric in the first place? Some say Dylan was inspired (or challenged perhaps) by an exchange he had with John Lennon. Dylan slammed Lennon, essentially dismissing The Beatles lyrically– “you guys have nothing to say”, was the message. Lennon’s counter was to enlighten Dylan of the fact that– he had no sound, man. Whether or not it resulted in Dylan going electric, or The Beatles writing more introspective lyrics, who knows– but it’s a helluva story.

*

Jerry Schatzberg’s shot of Bob Dylan in a New York studio. Unusual in that the singer is unguarded, and not posing for the camera – was taken in June 1965, during the recording of the Highway 61 Revisited album. Schatzberg was making his name as a fashion and portrait photographer when he got a call from Dylan’s then-girlfriend Sara Lowndes to say that if he wanted to take shots of the rising star and his newly acquired electric backing band, he was welcome. “Sara was a friend, and she and Nico [who later sang with the Velvet Underground] had been telling me about Dylan for a while,” remembers Schatzberg. “They took me down to see him play in the Village. After that, I was very keen to take his picture.” Schatzberg got to see a side of Dylan that was distinct from the one emerging in the public consciousness: he was playful, co-operative, and excited by the music he was making. “It was an ideal situation because he was absorbed by his work and he let me get on with mine. He was fun and willing to do anything, but he came across badly in the press at the time because the reporters’ questions didn’t match up with what he was thinking. I remember someone asked, ‘Do you believe in nature?’ His reply was, ‘I don’t believe in any drugs.'” The shot also coincided with Dylan’s denunciation by the folk world that had supported him. His performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, with an electric guitar and backing band, had outraged the acoustic purists, and he followed it with a tour that mostly consisted of sustained boos from the audience. “I went to see him in concert at Forest Hills in New York, where he was booed,” remembers Schatzberg. “We went to (Dylan’s manager) Albert Grossman’s apartment in Gramercy Park afterwards, and Dylan was in a rage because he was absolutely sure of what he was doing. It’s not the job of an audience to tell an artist what they can and cannot do.” A few months after the Highway 61 sessions, Grossman commissioned Schatzberg to shoot the cover of “Blonde On Blonde”, Dylan’s next album. “We went to the meatpacking district of Manhattan and all I remember is that it was cold. Some frames were out of focus, Dylan picked one of them for the cover, and that was that. I don’t get a credit, but I did get paid.”

*

“Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson. Knoxville, TN. Oct. 8, 1965” –Image via The Robert Bolton Collection. 8, 1965″

*

Dylan took the stage on Sunday with what was essentially the Paul Butterfield Blues Band– Mike Bloomfield on guitar, Sam Lay on drums, Jerome Arnold on bass, Al Kooper on organ, and Barry Goldberg on pian. They’d practiced with Dylan all Saturday night in a nearby mansion, but according to Kooper, “The Butterfield Band didn’t have the best chemistry to back Dylan… It (the practice) was a tough night… complicated and ugly”. Peter Yarrow introduced Dylan: “Ladies and gentlemen, the person that’s going to come up now has a limited amount of time … His name is Bob Dylan.” When Dylan and the band go into a loud, and raucous rendition of “Maggie’s Farm” the boos erupt almost immediately, along with mixed cheers. Then Dylan goes into “Like a Rolling Stone” (the week the song was released as a single) and the boos continue. After playing “Phantom Engineer” and still facing scorn from the crowd, Dylan tells the band, “Let’s go, man. That’s all”, and walks off stage– pissed and frustrated. A flustered Peter Yarrow returned to the microphone to try and calm things down, and along with Joan Baez manages to coax Dylan back on stage. Yarrow panders to the crowd by telling them Dylan is getting his acoustic guitar. Dylan is now ready to play for the crowd in an almost apologetic gesture– then there’s an awkward and tense appeal to the crowd for an E harmonica, followed finally by a classic Dylan rendition of “Mr. Tambourine Man” that gets things back on track for the folkies. It’s amazing to see Dylan do an about-face, reverting to acoustic, on a night when “going electric” was meant to be an epic artistic statement. And although the crowd exploded with applause at the end of Dylan’s forced acoustic set, he would not return to the Newport stage again for 37 years– and Ironically enough, the song they so fervently booed at Newport, “Like a Rolling Stone”, was named by none other than Rolling Stone magazine as the greatest rock song of all time.

*

*

*

*

*

Circa 1963, Greenwich Village, NY– Bob Dylan. Much has been made about why Dylan chose to roll a tire for this photo shoot in New York in 1963. But Marshall insists there was no cryptic reasoning for it. “He just picked up a tire that was nearby and rolled it, that’s the end of it.” –Photograph © Jim Marshall

*

Bob Dylan, early 1960s. –Photo by Michael Ochs Archives

*

Bob Dylan –Photo by Jerry Schatzberg

*

(Left) Circa 1965, NY– Bob Dylan Recording in Studio –Image by © Jerry Schatzberg/Corbis

(Right) Circa 1966, Denmark– Bob Dylan contemplates Kronborg Castle, the Elsinore Castle of Shakespeare’s , shortly after arriving in Denmark to start his world tour. –Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

*

Bob Dylan in 1968-1969. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

*

1965, New York, New York, USA — Bob Dylan Exhaling Smoke — Image by © Jerry Schatzberg/CORBIS

*

Circa 1966, London– Bob Dylan, fans looking in to limousine –Image © BARRY FEINSTEIN. Via

*

Check out the legendary 1965 San Francisco press conference, with Allen Ginsberg in the audience heckling Dylan–

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

He went electric at a folk concert – True, but it was several years after Muddy Waters (among many) played electric at Newport..

It’s hard for young people like me to understand what was so bad about it but I think he had such a huge folk fan following then that when he went electric (I think Newport folk festival was one of the first) like He had betrayed his folky roots but nothing can beat his 1966 performance of Like a Rolling Stone. If all electric music was like that then damn…

Yeah, I know it is hard to understand what the big deal was, considering that nothing is shocking anymore.

Like you said, the context of the event is crucial- Consider what the Newport crowd wanted/expected of Dylan at that time, along with the fact that it was a Folk Festival and he basically came out on stage to blow them away (with Mike Bloomfield wailing on lead guitar), and the sound was LOUD and poor.

Pete Seeger said if he’d had an axe, he would’ve chopped their cables on the spot. Some say he made that comment simply because he was outraged Dylan went electric- Petes now says it was because Dylan’s voice was inaudible from the fuzz and feedback and was upset that the crowd was not able to “hear” Dylan’s important lyrics.

JP

I was once reading a column in Time magazine about the top 100 most influential people of the twentieth century . Right up there with Einstein was Bob Dylan and I quote, ” he moved a generation along like a VW in the wake of a semi.” for me Bob Dylan is the epitome of Americana song writing. and will leave an indelible mark on musicians . In my humble opinion he rocks . At fifty I still haven’t heard another as poignant.

i agree with you, very well put.

Pingback: The Selvedge Yard on Dylan | The Reference Council

Pingback: Top Posts — WordPress.com

It’s always difficult to get context about something that happened so far in the past – even though it seems like yesterday to me. Pop music went through an awful lot of changes from the ’40s, when I figured out how to turn on a radio as a toddler, to the ’60s. Can you imagine what I encountered in 1945?

I was lost in Basie and Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald long before I started school, and even in the early ’50s you could find Thelonious Monk and Flatt and Scruggs if you looked hard enough. Pop music had decayed by that point to the level of fluff like “Come Onna My House” and “Hot Diggity Dog Ziggity,” and even Les Paul’s early stuff with Mary Ford sounded so processed you couldn’t believe there was a guy back there playing it. And Les was always hard to believe anyway. When the rock ‘n roll boom took over the planet in the late ’50s and early ’60s it seemed like all the cool kids just couldn’t get enough of it – and the rest of us just hid out with our weird record collections.

The Folk Scare, as Garcia termed it, offered stuff that sounded like it was made by people like us, and a helluva lotta geeks started learning how to play the guitar. Think of it as Version 1.0 of Revenge Of The Nerds. We’d heard nothing but electric guitars played by guys in slick haircuts for the last 5 or so years, and this music sounded like it was possible for normal people. There’s a sound that happens in the air between an instrument and the microphone, and the concurrent leaps being made in recording technology from Monaural to Stereophonic were all about capturing live sound as if you were in the same room with it. Electric instruments are all about a sound that is produced by the speakers, and it sounds flat instead of three-dimensional once you’ve heard “acoustic,” for want of a better word, music produced in real air in your real presence. And of course a lot of people in ’65 were invested in stuff that had little to do with the music anyway, so they probably did feel “betrayed” in some way.

Joan Baez was and is a phenomenal musician by any standard, I think, whatever I may think of her “message.” And Bob Dylan crafted pearls like “Girl From The North Country” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”, “Take Me As I Am” and “Lay, Lady, Lay” before and after his “protest song” period, which is evidence enough of why he might have felt stifled by Pete Seeger and the other bards of The Movement. The Folk Boom was a brief moment in time, and a lot of people got tired of being preached to real quick, so it didn’t take any time at all before there was a huge audience for Dylan’s electric stuff. Didn’t care for it myself, but it was certainly a relief.

One more unasked-for opinion about sound: I’ve been a singer and musician just about my whole life, and I’ve heard about every kind of speaker and sound system. Still, the most powerful and exciting sounds I’ve ever heard were while playing in a hot Bluegrass band in the open air with no mikes, or singing Bach arias in the middle of a Baroque orchestra that was similarly unamplified. Nobody had any trouble hearing it because the players and singers did the balance with their own ears, and the audience, surprise surprise, shut up enough to hear something they wanted to.

I think Dylan “going electric” at Newport was the wrong act in the wrong place, and I think he knew that and didn’t care. And I’m pretty sure that a lot of the “reaction” came from folks who were afraid all that noise meant the end of public performances where people came to listen. And I think they were right, too.

Super-engineer Roy Halee (Simon & Garfunkel, Blood Sweat & Tears, etc.) said that the best sound was always obtained by having a band play live around one microphone. I don’t agree 100% but I admit he knows what he’s talking about.

Great post as always. I am the proud owner of a copy of Sing Out! magazine when they reviewed Bob’s electric showcase at Newport. They weren’t too happy about it FYI.

Many thanks for this great read.

Though not much of a “folk” listener these days, I discovered BD as a young high school student in ’71. I think I had his “greatest hits’ double LP, and I wore that thing out. these days, I appreciate his poetry more than ever, though I wonder how, back in the day, I could endure hours of his nasal vocals on a scratchy LP. though I agree with an earlier post on the depth of his influence in the 20th century, I think his music, especially the early stuff, is best when covered by others… try listening to Abbey Lincoln’s “Mr. Tambourine Man”, or Maddie Peyroux’s “Your Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go” and you’ll know what I mean. aloha, Don

As in most of Dylan’s early choices, his guitar was a lot like Woody Guthrie’s, who usually played a similar size and shaped Gibson.

I think a lot of people were disappointed with Dylan, not only for the electricity, but because they were losing a dynamic and charismatic figure that could have led them in their political and social struggles. Seems like Dylan realised the pitfalls of being a player on that stage, especially after seeing his president assasinated and did not want the responsibility or risk to his life.

He not only plugged in, but tuned out, meaning he stopped being a topical singer and wrote more commercially viable music. I cannot help but think he knew what he was doing at Newport, such a divisive move could not have been un-premeditated on his part. He’s too clever for that.

Mr. De Witt,

I think you hit the nail on the head in saying that the music wasn’t really the point to the hard-core purists who felt betrayed by Dylan. It quite obviously had more to do with politics than music for them. That faction has been trying to draft Dylan into service for decades but he has always resisted it. He refused to be used for their political purposes. He may have written protest songs but, especially lately, his music is really what matters. He considers himself a musician, first and foremost. He’s not kidding when he says he is a song and dance man. The last 4-5 albums are the most musically interesting of his career and there isn’t any “protest” or politics in them. Just deep, interesting, sophisticated songs that couldn’t have been written by anyone but Dylan.

I don’t know . . . love him or hate him, Dylan is always exactly who he is. I deeply respect him for that. There is no artifice. He follows his own path and you can’t ask anything more from an artist. It sounds cliche but we should just be thankful to live in a world where every few years a new Dylan album comes out. I know I am.

it is sad that a political agenda would be pushed on someone like Dylan. Songwriters are creative ARTIST and if they have a political tone so be it – be trying to steer an artist is a bad bid man.

Another GREAT post. In the words of Chicago, “You’re the inspiration” to our blog/magazine. We even wrote an ode to The Selvedge Yard.

Check it out here: http://theocgazette.blogspot.com/2010/01/some-of-what-youll-find-at.html

Thanks for helping me to live in the past 🙂

Pingback: TIME FOR A CHANGE | ERIC CLAPTON, THE BAND, AND MUSIC FROM BIG PINK « The Selvedge Yard

I was fortunate enough to have been at Newport Folk Festival in 1965 “when Dylan went electric”. Actually, this was no surprise to the audience, most of whom had been there for a couple of days and could hear Dylan and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band rehearsing during the previous day. For some reason, in the accounts I have read since of this “epic event”, this is never mentioned. This supports the contention mentioned already in earlier posts that the booing of Dylan when he and Paul Butterfield et al appeared on stage was political. The folkies had lost Bobby and they were real mad about it.

I’m afraid that Bob, who is a genius, does not have great people skills and he is responsible for rubbing his musical changes in the faces of Newport’s folk audience on that “fateful day”. He appeared on stage in leather like Elvis, not in his usual Woody Guthrie/Pete Seeger work shirt attire and proceeded to rip into “Maggie’s Farm”. This was very shocking to some, but not to me. I thought it was great and ran down the aisle to get close to the stage and cheer him on.

In one fell swoop, Bob ushered in the age of “Folk Rock”, a term he despised. He was right: is “Just Like A Woman” a folk rock song or an amazing song? Is “I Got You Babe” by Sonny and Cher a folk rock song? Maybe the Byrds versions of “The Bells of Rimney” and “Turn Turn Turn” are folk rock songs. Are the Mamas and Papas folk rock? It all gets a bit silly after awhile, all this defining of musical rock genres and putting complex musical artists into boxes that can be easily marketed.

The thing about 60s music is that it encompassed everyone: The Doors, Jimmy Hendricks, the Rolling Stones, The Beatles, The Byrds, Richie Havens, Credence Clearwater, The Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Joanie Mitchel, Joan Baez, Laura Nyro, Donovan, Eric Clapton & Cream, the Band etc. It was all MUSIC period, and it was created by young people who were singularly unique!!

And without Bob Dylan, I don’t think that any of this musical outpouring would have happened. By staying true to his artistic vision, he gave other musicians the permission to do the same — to master their instruments, write down their thoughts, feelings and opinions, draw from existing American musical forms like jazz, blues, bluegrass etc and put it out there.

I think people blow this out of proportion. I have recordings of alot of those early electric shows including his first one at Newport in ’65, and you don’t hear a single boo from the audience, In fact at his first show they sound pretty blown away by his performance.

Besides that, Bo Diddley and Muddy waters used to play those folk festivals plugged in and everybody seemed to enjoy that alright.

The only recordings I’ve ever heard from that period where the audience is hostile were of British audiences like the royal albert hall gig!

Don’t forget that Bob played rock and roll in high school during the 1950’s. The music was in his blood just as much as folk music or blues was. It’s been said that when he heard the Animals cover “The House of the Rising Sun” it was almost as big an influence on him turning to rock as the Beatles – perhaps because he sang and recorded that song earlier in his career. By ’65, the writing clearly was on the wall, he was going electric whether his fans liked it or not. Good thing too, the music he made in ’65-’66 is some of the greatest of his career.

I was there in 1965. What most people don’t realize (and only a few observers seem willing to note) was that Dylan chose one of his worst songs (Maggie’s Farm) to usher in the age of electric folk rock. Maggie’s Farm is a monotonic rant with maybe two chord changes per verse, hardly the best stuff to publicize a new genre. With a poorly tuned sound system to boot, this was not destined to go over well with an audience that wasn’t totally sold on electrified folk to begin with. I think if you listen carefully to the tapes that now exist, you will hear that the boos came to a stop almost completely when he shifted into the quieter, more melodic “Like A Rolling Stone”. I have always contended that if he had opened with “Like A Rolling Stone” instead of “Maggie’s Farm” there would not have been the notorious reaction that occurred.

I remember the controversy. In retrospect, the acoustic sound FAR surpasses most electric stuff. As artists, we can only engage the journey, but Dylan’s lyrics got tedious when he paid more attention to style than substance. I might have wanted to yank the plug myself, back in ’65.

marko, maggie’s farm is the most appropriate song dylan could have chosen for this moment, because what the electric band was most about was dylan’s refusal to toe the folk purist political party line. he had a “headfull of ideas” that were drivin him insane, and he wasn’t going to continue to just do the done thing or what was expected of him.

“Well, I try my best

To be just like I am

But everybody wants you

To be just like them

They say sing while you slave and I just get bored”

etc